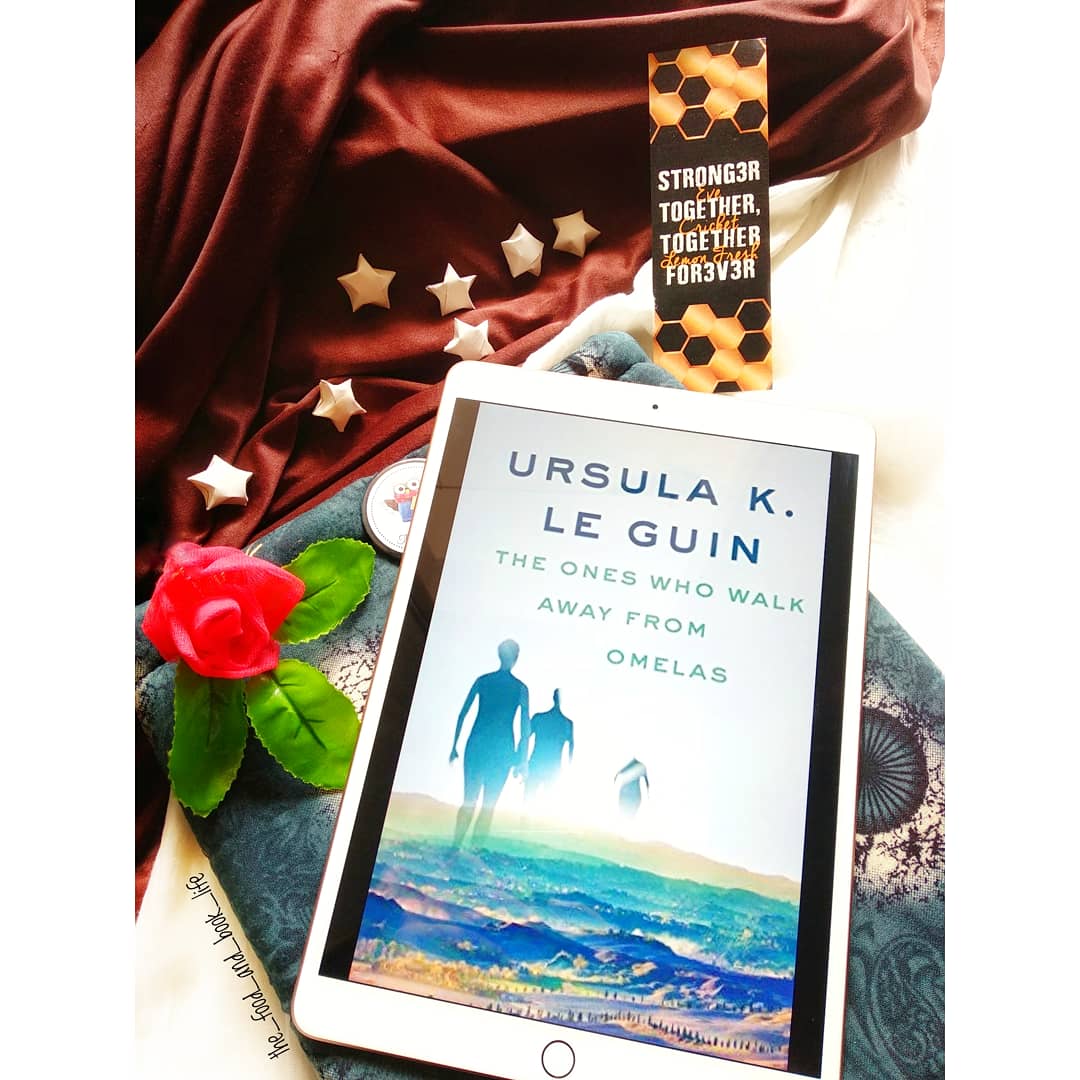

For instance, how about technology? I think that there would be no cars or helicopters in and above the streets this follows from the fact that the people of Omelas are happy people. Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids, assuming it will rise to the occasion, for certainly I cannot suit you all. Omelas sounds in my words like a city in a fairy tale, long ago and far away, once upon a time. O miracle! but I wish I could describe it better. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched. How can I tell you about the people of Omelas? They were not naive and happy children-though their children were, in fact, happy. We have almost lost hold we can no longer describe a happy man, nor make any celebration of joy. But to praise despair is to condemn delight, to embrace violence is to lose hold of everything else. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.

Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Yet I repeat that these were not simple folk, not dulcet shepherds, noble savages, bland utopians. As they did without monarchy and slavery, so they also got on without the stock exchange, the advertisement, the secret police, and the bomb. I do not know the rules and laws of their society, but I suspect that they were singularly few. Given a description such as this one tends to look next for the King, mounted on a splendid stallion and surrounded by his noble knights, or perhaps in a golden litter borne by great-muscled slaves. Given a description such as this one tends to make certain assumptions. But we do not say the words of cheer much any more. They were not simple folk, you see, though they were happy. Joyous! How is one to tell about joy? How describe the citizens of Omelas? In the silence of the broad green meadows one could hear the music winding through the city streets, farther and nearer and ever approaching, a cheerful faint sweetness of the air that from time to time trembled and gathered together and broke out into the great joyous clanging of the bells. There was just enough wind to make the banners that marked the racecourse snap and flutter now and then. The air of morning was so clear that the snow still crowning the Eighteen Peaks burned with white-gold fire across the miles of sunlit air, under the dark blue of the sky. Far off to the north and west the mountains stood up half encircling Omelas on her bay. They flared their nostrils and pranced and boasted to one another they were vastly excited, the horse being the only animal who has adopted our ceremonies as his own.

Their manes were braided with streamers of silver, gold, and green. The horses wore no gear at all but a halter without bit. All the processions wound towards the north side of the city, where on the great water-meadow called the Green Fields boys and girls, naked in the bright air, with mud-stained feet and ankles and long, lithe arms, exercised their restive horses before the race. Children dodged in and out, their high calls rising like the swallows’ crossing flights over the music and the singing. In other streets the music beat faster, a shimmering of gong and tambourine, and the people went dancing, the procession was a dance. Some were decorous: old people in long stiff robes of mauve and grey, grave master workmen, quiet, merry women carrying their babies and chatting as they walked. In the streets between houses with red roofs and painted walls, between old moss-grown gardens and under avenues of trees, past great parks and public buildings, processions moved. The rigging of the boats in harbor sparkled with flags. With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city Omelas, bright-towered by the sea.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)